Once upon a time...

As far the eye can see, nothing stands between Villa Lattuada, isolated in its green oasis, and the distant peaks of the Resegone and the Grigne mountain range.

“It is impossible to describe the elegance and attractive quality of the Villa. One’s eyes never tire of the view and sublime air of this enchanting sojourn, with its picturesque backdrop of distant mountains and nearby rolling hills that refresh and rejuvenate one’s vision” (so wrote an unknown author in Ville e Castelli d’Italia, 1907).

The origins of this distinctive and poetic place go back to the annals of history.

Villa Lattuada is situated on the so called “Four Valleys” bluff where historic St. James Priory once rose. At the beginning of the 1500s, the Dominican Friars of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan built the small priory on the grounds of a pre-existing XIII century country chapel dedicated to Saint James the Apostle (mentioned in 1288 by Gottofredo da Bussero in his “Liber Notitiae Sanctorum Mediolani”). Filippo Maria Sforza, the second born son of the Duke of Milan, Francesco Sforza and Bianca Maria Visconti, helped financially its construction of the monastery with a legacy of over 200 ducats; other monies bequeathed over time, increased the property holdings.

Fra Michele Ghisleri, a Dominican prior and inquisitor general for Lombardy, often spent long periods of rest at St. James. In 1567, the year after he was elected Pope Pius V, he granted a 7 years’ indulgence to all those who visited it.

In 1652, the papal directive of Pope Innocent X decreed that the members of religious communities of fewer than 6 monks be aggregated in large houses for each Order, thus effectively suppressing small monasteries such as that of St. James. In the midst of the vicissitudes to re-establish and then suppress the priory, the Friars of Saint James continued their mission of preaching the faith and teaching the male children of Casate to read and write. In 1785, the property was put up for sale. Two noble brothers, Don Apollonio and Monseigneur Don Giulio Casati bought the monastery which was then deconsecrated and closed. This effectively put an end to its long and productive history, leaving behind the memory of a place well-loved by all.

A castle, or perchance a flight of fancy

In more recent times...

Between 1883-1885, Giuseppe Lattuada commissioned an architect from Brescia, Antonio Tagliaferri,to design and build the extraordinary Villa Lattuada right on the “Four Valleys" bluff overlooking the distant Resegone and Grigne mountains where the ruins of the old priory stood. The villa, perhaps one of his finest buildings, is a fascinating synthesis of eclectic and romantic styles with elegant white marble embellished facades and two castellated panoramic towers. Its pinnacles, pointed gables and steeply slanting ridge roof bring to mind German castles and Gothic cathedrals, the great architect’s distinctive hallmark. Tagliaferri satisfied his taste for faithfully reconstructing a manor house as best he could, by inserting so many different Tudor-style architectural elements that, as he wrote in 1881, “one feels obliged to bow and think of queens, ladies-in-waiting and pages; the Villa evokes the same fantasies as does the reading of historic novels or the glimpse of ruined crenellated castles.”

Tagliaferri’s architecture was grandiose in style and new to the Brianza area where the tradition of building stately villas was more commonplace; however it was a style that blended perfectly into the surrounding romantic countryside. Even King Umberto I was so taken by the incomparable view and fascination of the regal villa that he chose it for his clandestine sojourns.

From afar Villa Lattuada appears suspended between earth and sky: a gleaming castle to watch over the tranquil Lombardy countryside.

CARLO VARESE, Landscape around Casate Novo, oil on panel, 750 x 1500 mm, private collection.

The plan for Villa Lattuada as described in the papers of Antonio Tagliaferri

by Irene Giustina*

The romantic air and Neo-Medieval features of Villa Lattuada, inspired by late Anglo-Saxon Gothic styles, give it, as illustrated, a character unique to the panorama of 19th century residences in the Brianza area.

Thanks to previously unseen documents, drawings and photographs found in the Tagliaferri archives, recent research has taken another look into the history of this fanciful villa and its surrounding garden. These archives are presently conserved at the Fondazione Ugo Da Como in Lonato del Garda in the province of Brescia, along with papers and images made available by the current owners of the Villa and other public and private archival institutes. This collection sheds light on the Villa’s initial project and construction stages which up to now were only summarily known, to give a more grounded interpretation of the unusual formal and expressive choices made by Antonio Tagliaferri, the renown Brescia architect.

New studies reveal that this splendid Villa was built between 1883 and 1885 upon the initiative of Cavaliere Giuseppe Lattuada, a wealthy Milanese entrepreneur in the textile industry. He wanted to build a new country manor atop the panoramic knoll known as the “Four Valleys” overlooking Casatenovo, thus extending his father’s estates, site of a more

modest villa, towards the ruins of the old Dominican priory of Saint James. Wishing to clearly consolidate the financial and social status he had attained, Lattuada, following the established usage of wealthy upper class entrepreneurs at the time, conceived his villa on a monumental scale like the opulent villas built by the Milanese aristocracy in the Brianza area where they historically settled. Antonio Tagliaferri (1835-1909), the most well-known architect in Brescia in the late 19th century, was commissioned to make Lattuada’s dreams come true. Tagliaferri had distinguished himself through numerous works haracterised by his historicist approach, open to all styles but with a certain predilection for medieval ones, and to almost all fields, ranging from restoration of monuments to new constructions, from urban development to furniture.

Tagliaferri, an exceptional draughtsman trained at Milan’s Brera Academy of Fine Arts, had always maintained a close relationship with it, first as an Honorary member then as a Councillor. He was also quite active professionally in Milan where he came in contact with Camillo Boito and all the protagonists of the architectural culture of the day. From 1887 onwards he devoted himself principally to residential buildings, starting with several major projects in the centrally located upscale area of Via Dante and Foro Bonaparte in collaboration with Giovan Battista Casati and Giuseppe Magni. Tagliaferri’s name grew in popularity thanks to his project for the Brescia Pavillon at Milan’s Italian National Industrial Exposition held in 1881. The Pavillon with its 14th century Gothic style features and romantic elements alluding to the idea of the castle, found favour with the general public and ensured Tagliaferri’s fame as an artist “enamoured of Medieval times.” These features may have influenced Giuseppe Lattuada, amongst the Exposition organisers, and his choice of a style for his new country manor that was vaguely reminiscent of castles as portrayed in the plays and literary works the wealthy upper class particularly appreciated at the time.

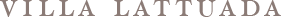

Antonio Tagliaferri, initial design for Villa Lattuada, watercolour of the north elevation. Casatenovo Brianza.

Private collection.

For his first professional commission in Milan, Tagliaferri, was more than pleased to fully indulge Lattuada wishes. He drew up a two-step monumental plan for Villa Lattuada reconciling its Gothic style exterior, often depicted in fine watercolour paintings and drawings, with the technical efficiency, functionality and living comfort, indispensable features of stately homes. To do so, he reinterpreted and amplified the traditional Renaissance block style villa, putting the kitchens and Villa facilities and services in the basement. On the ground floor, the reception rooms were centred around a grand floor-to-ceiling atrium illuminated from above by a wrought iron and glass skylight; the master suites and servants’ quarters were put on the first and second floors respectively.

Leading off the west entrance foyer on the ground floor were the spacious and lavish library and smoking rooms intended for the master of the house; the south entrance opened onto the dining room and adjacent pantry, whereas the reception rooms, flanked by the “winter garden” and the billiard room, opened onto the east veranda, considered to have the most panoramic view. The main staircase, moved to the left of the north entrance hall, led up to the master suites on the piano nobile and the galleries overlooking the atrium.

Tagliaferri cleverly concealed the regularity of the building’s square plan by adding bow-windows, staircases, porticos and projecting terraces to the Villa exterior. Spires, pinnacles and buttresses of varying heights were placed on its roof to give the building a strong vertical profile; the towers at either corner of the west wing and prominent crenellations, lent the Villa a castle-like air. The predominant use of Tudor arches, English-style crenellations and Botticino marble moulding crafted by Lombardi, one of Brescia’s most well-known quarries, marked the architect’s return to his repertoire of the long-established Northern Europe and British Late Gothic styles for both the Villa exterior and its furnishings which often replicated those featured in the Exposition of 1881. The overall effect, modelled after the Anglo-Saxon Tudor style in fashion in Milan

then, was achieved through the skilful employment of architectural elements typical of castles, aristocratic country manor houses and middle class “cottages.” This same style was also reflected in his design for the landscape park, with its carefully laid out English-style garden that was finished in September of 1885, the month in which the Villa was inaugurated.

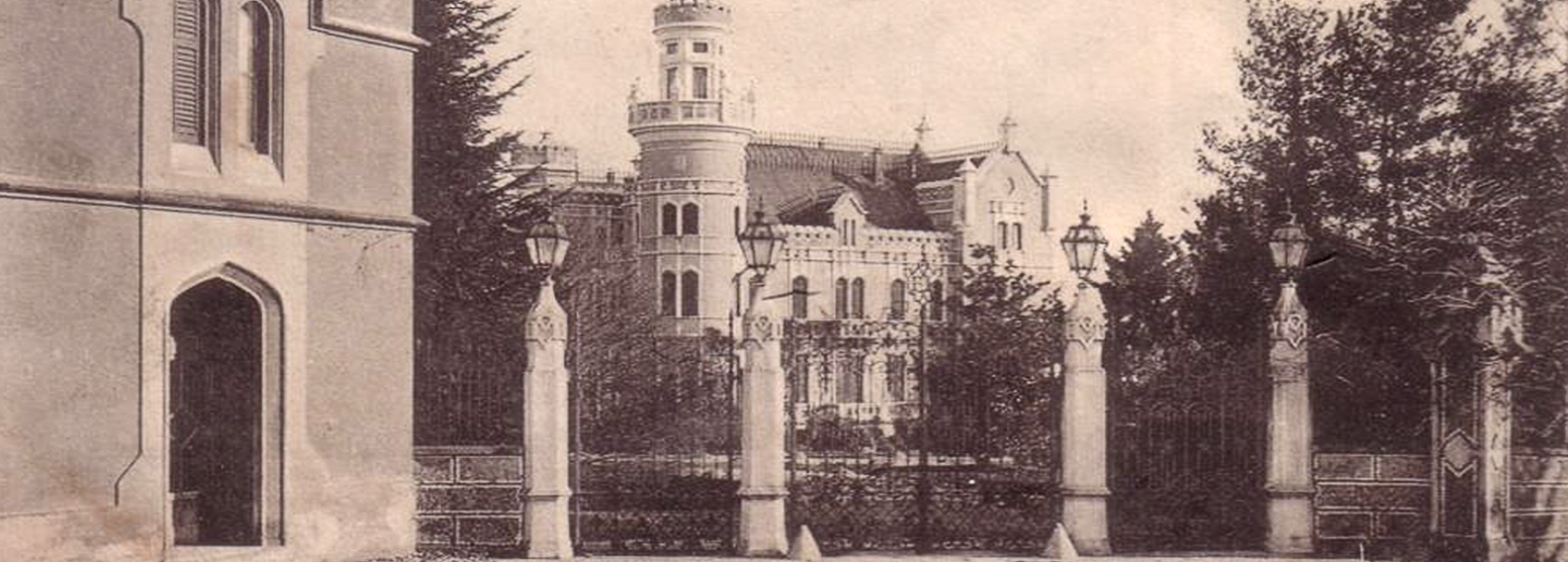

Achille Ferrario, photo of the recently completed Villa Lattuada and its landscape park (1885).

Tagliaferri Archives, Fondazione Ugo Da Como - Lonato del Garda (BS).

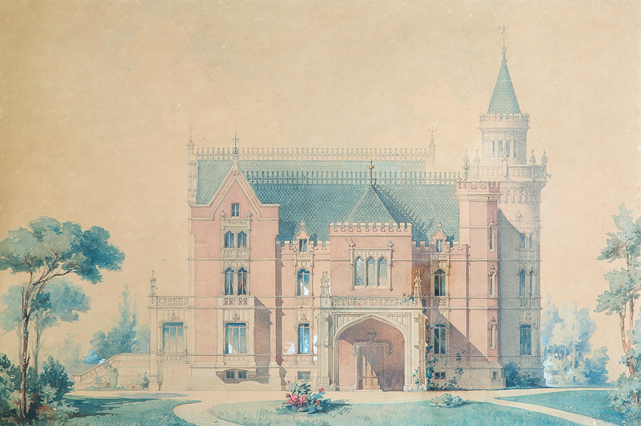

Tagliaferri’s interiors had already been subject to an initial renovation at the beginning of the 1900s. Between 1901 and approximately 1907 when the initial romantic momentum had exhausted itself, the Lattuada family itself decided to modernise the Villa rooms under the supervision of the celebrated Royal Architect, Marquis Achille Majnoni d’Intignano. Recent studies backed by correspondence and striking photos, document how he adapted the interior decor of the Villa to the 18th century Neo-Baroque style which was commonly found in the Brianza area by the late 19th century after the modernisation of the Monza Royal Palace. This may have informed the Lattuada’s choice for the decor of their Villa as they were keen to follow the fashions dictated by the Monza Palace, scarcely 15 km away. In fact, since King Umberto I and his Court spend their summers in Monza, the family probably had a close friendship with the king who was an occasional guest at Casatenovo, as attested by his signature in the Guest Book still preserved at the Villa today.

View of reception room on the ground floor after Achille Majnoni’s renovation. Private collection.

The 19th century restyling is by now lost. Subsequent changes to the Villa, even the most recent ones that transformed part of it into a reception and conference venue, have left unchanged the extraordinary expressive coherence of its original architecture and surrounding landscape park. The Villa today remains as charming as ever with its sophisticated Italian architectural features that Tagliaferri ably combined with his own repertoire of Anglo-Saxon and Northern European late-Gothic styles, harmonising them into his picturesque and fanciful late 19th century Gothic Revival Villa.

* Irene Giustina is Associate Professor of Architectural History in the Department of Civil, Environmental and Architectural Engineering and Mathematics - DICATAM at the University of Brescia. Her recent research has focused on eclectic historicist architecture and the works of Antonio Tagliaferri. The results of her new studies on Villa Lattuada are extensively described in the article, I. GIUSTINA, «Particolari Tudor su un corpo classico». Il progetto di Antonio Tagliaferri per la Villa Lattuada a Casatenovo Brianza (1882-1885), in «Arte Lombarda», 186-187, 2019, n. 2-3, pp. 155-176, whereas the architect’s activity in the Milanese context is explored in the monograph, I. GIUSTINA, Antonio Tagliaferri e l’architettura residenziale nella Milano borghese. Progetti, stili, alzati (1887-1909), CaracolEdizioni, Palermo, 2020.

The Villa Lattuada Collection of Works of Art

by Olga Piccolo*

The fortuitous discovery of several annotated copies of the catalogue from the first Alfredo Geri auction in Milan (1916), gave impetus to further research in the Villa’s collections. Geri was the Florentine antiques dealer who became well-known for his role in recovering Leonardo’s Mona Lisa and returning it to the Louvre after its theft in 1911. According to the catalogue’s title page, “a significant collection of ancient and modern art previously owned by an eminent Bergamo-born nobleman” was to be put up for auction, making it possible to identify the nobleman as Costanzo Cagnola (1867-1925), cousin of the more well-known Guido (1861-1954), who organised the collection still kept today at Villa Cagnola di Gazzada (Varese).

Costanzo, lawyer and businessman, and remembered in the 1950s by Massimiliano (nicknamed Max), the young son of Architect Achille Majnoni d’Intignano, as being “reckless and a liar but likeable”, was forced to sell the art works he had amassed from his paternal and maternal families and from the Lattuada family of Casatenovo (Lecco).

During research carried out at the Historical Library of the Brera Fine Arts Academy in Milan, another copy of the catalogue from the Geri auction came to light. On this title page of this copy, there is a handwritten inscription in ink, “Don Costanzo Cagnola - Latuada [sic] et al”. Using this as a starting point, and thanks to other cross-references uncovered during the research, it was possible to confirm that prior to the auction sale, the Lattuada and Cagnola families had agreed to jointly auction off several works of art from their respective collections in an anonymous form.

Costanzo had married Elena Mazzucchelli, the sister of Clementina Mazzucchelli Lattuada. The discovery in the Vismara Archives in Casatenovo of the “Quattro Valli / Visite 1890-1936” guest book of visitors to Villa Lattuada di Casatenovo enabled the visits the cousins Costanzo and Guido Cagnola paid the Villa from 1890 onwards, to be documented, thus demonstrating a relationship between the two families that predated that of kinship. Costanzo’s signature in the album can be found again in 1891, 1896 and 1898, attesting to his regular presence at the Villa at the end of the 1800s.

In 1903 Costanzo founded his Milan-based chemical and pharmaceutical industry, “C. Cagnola & C.”. The company which advertised itself as the best known brand of effervescent granulated citrate, was active until 1911.

Research conducted at the Historical Archives of the Milan Chamber of Commerce showed that the Honourable Giuseppe Lattuada, a Milanese entrepreneur in the textile industry as well as owner from the second half of the eighteenth century, of the remarkably expressive and original Neogothic style villa, ‘Villa Lattuada, (known as Villa Vismara today), was elected to the company’s first Board of Directors in 1903. Giuseppe Lattuada was also the husband of Clementina Mazzucchelli.

The most recent research on the Villa has been carried out by Professor Irene Giustina who reconstructed the planning stages and formal choices made during its construction by studying unpublished documents in the Archives of Antonio Tagliaferri (see the text above).

As a result of inquiries to the Majnoni d’Intignano Archives in Marti, Montopoli Val d’Arno, Pisa, as well as to other archival and photographic collections, it was determined that at least two of the works of art put up for auction in 1916 belonged to the Lattuada collection and had been kept in their villa in Casatenovo. Most certainly these were certainly the Madonna con Bambino (Madonna and Child) by Bartolomeo Veneto and the fresco by Pier Francesco Mazzucchelli, known as Il Morazzone, entitled La Fucina di Vulcano (Vulcan’s Forge).

From the contents of a letter written by Clementina Lattuada to Achille Majnoni dated November 30, 1916, it was possible to assume that “the President of the Metropolitan Theater [sic]” of New York (the Metropolitan Opera House), “an extremely wealthy person”, had already expressed his desire to acquire through Giulio Setti, director of choir at the Metropolitan and “a great friend of the Cagnola family” (Majnoni d’Intignano Archives, Marti, Achille Majnoni Foundation, 162.2, Clementina Lattuada Letter n. 192), a significant number of Lattuada-Cagnola paintings in the spring of that year, that is several months before the Geri auction. The President of the Metropolitan Opera House in all probability can be identified as the American banker and philanthropist, Augustus D. Juilliard (1836-1919), who was particularly interested in acquiring the Bartolomeo Veneto painting.

In the presentation of the Geri catalogue, the painting was highlighted as one of the principle masterpieces to be auctioned, and another annotated copy of the catalogue found in the Library of the Carlo Ludovico Ragghianti Foundation in Lucca commented that during the auction, a bid of 39,000 Lire, a considerable amount of money for that time, was made to acquire this painting.

In the letter that Clementina wrote to Achille she also stated that the painting went unsold; in fact the auction took place during the difficult and tempestuous times of World War I. Clementina was in doubt whether to sell the painting in America to Juilliard at a higher price, risking that the transaction be “considerably” protracted, or more prudently in Milan through Achille Majnoni who had already found an interested collectivist.

From another letter dated February 27, 1920 that Clementina’s son, Francesco (called Franco) wrote to Achille Majnoni (Majnoni d’Intignano Archives, Marti, Achille Majnoni Foundation, 162.2, Franco Lattuada Letter n. 5), it came out that negotiations for the painting were never completed and that the work of art remained in the hands of the Lattuada family who kept it in the villa in Casatenovo. That same year, however, it was Franco who sold it through the good offices of Architect Majnoni, who in turn proposed it to the Crespi family in Milan with whom he had been collaborating for several years as an architect.

Bartolomeo Veneto, Madonna con Bambino (Madonna and Child), 1520-1530 ca., oil on board, 64 x 44.5 cm.

Private collection. Image from the 1916 Geri auction catalogue, figure 41.

This painting was shown at the first exhibition of Old Lombard Masters held in Milan in 1923 as part of the collection belonging to Giulia Crespi Morbio subsequently inherited by Vittorio Crespi Morbio. In 1957 Bernard Berenson remembered having seen the painting in the Aldo Crespi Collection. During the research it was traced to a private collection in Milan.

Pier Francesco Mazzucchelli, known as Il Morazzone, La Fucina di Vulcano (Vulcan’s Forge), fresco removed and placed on canvas, 202 x 265 cm.

Sforzesco Castle of Milan Picture Gallery.

The fresco, removed from the house in Morazzone (Varese) which tradition says was the painter’s home, was originally painted on the wall above the chimney within a plaster framework. In 1874 the building passed into the hands of the Lattuada family and the fresco was placed in a solitary room in the centre of the garden where it remained at least until 1892. No later than 1896, the family had it detached from the wall by an art restaurateur from Bergamo.

After the auction of 1916, La Fucina di Volcano (Vulcan’s Forge), the highest bid for which reached 14,000 lire, remained unsold and was returned to the Casatenovo villa. The fortunate find of a series of photographs from that period has allowed the fresco’s presence to be documented inside Villa Lattuada where the painting, the Portrait of Clementina Mazzucchelli Lattuada (Ritratto di Clementina Mazzucchelli Lattuada), was also kept.

Morazzone’s painting inside Villa Lattuada di Casatenovo (Lecco) in a photograph ante 1929. Private collection.

The fresco remained in the Lattuada collection until 1929 when the Sforzesco Castle of Milan acquired it from the Lattuada family. The fresco can still be found today in the museum picture gallery.

These are just some of the loose ends that, tied together, lead to the considerable amount of art collecting that took place between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in Lombardy, a topic which has remained unexplored to date and which will be given further consideration.

*Olga Piccolo After attaining her degree in the History of Medieval Art, she obtained a post graduate diploma in the History of Modern Art and a PhD in the same discipline. She specialises in historical-artistic research, with a particular focus on the Lombard-Venetian Renaissance, on the dispersion of works of art during the Napoleonic age and on the history of art collecting in the XIX century. She has dedicated many scientific and academic publications to these subject matters, and collaborated with the Minister of Culture in projects to protect and valorise the historical-artistic patrimony of Italy.

The vicissitudes in reconstructing the Lattuada collection, briefly summarised above, are dealt with at greater length in the monograph; O. PICCOLO, La collezione disperse. Le opera Cagnola-Lattuada prima e dopo l’asta Geri del 1916, with comments by S. Bruzzese and preface by A. Rovetta, Scripta Edizioni, Verona 2023